-

A player piano, commonly known as a "pianola", is a piano containing additional mechanisms that allow it to perform music without a pianist. They were most popular between 1900 and 1930, before gramophones and radio became popular and refined enough to push the player piano into obscurity.

-

Player pianos are often known as pianolas, although the Pianola was in fact a trade name for a particular brand of player piano produced by the Aeolian Corporation. The player piano uses suction and air pressure to operate the player mechanism, which is provided using either an electric motor, or more commonly generated by foot pedals connected to a large bellows contained within the lower part of the piano. The operator uses his or her feet to push two foot pedals. Doing this produces suction in the bellows, which is then distributed to 88 tubes (one for each key). The air also pushes the paper roll ("piano roll") over a metal bar (the 'tracker bar') which also has 88 holes, with the tubes connected behind. When a hole in the roll passes over a hole in the tracker bar, the air is admitted into the system, causing that key to drop down and make a sound. The operator may also introduce dynamics, phrasing, and expression into the music, if they wish, by varying the force of their pedalling and moving the various control levers - this enables them to introduce their own musical interpretation into the music, regardless of whether they're able to play the piano themselves or not.

When a piano roll is playing, the piano keys move as if an invisible pianist is present. (see video below)

The 'reproducing piano' is an advanced variety of player piano, which contains additional mechanisms that enable it to automatically vary the dynamics of the music in response to additional perforations in a reproducing piano roll. This enables it to reproduce music exactly as it was played by the recording pianist, rather than rely on the player piano operator to vary the dynamics. These reproducing pianos were much more expensive than a regular player piano, and were generally found in the houses of the wealthy during the original era of popularity of the instruments.

What is a Piano Roll?

A piano roll is a roll of paper perforated (punched) with holes that operates a player piano (pianola). The location, position, and length of the perforations determines what note of the piano is activated and how long for. Combined, the perforations produce a performance of a piece of music. In the 1920s, a typical standard 88 note roll retailed for between 50c - $1.25, depending on the manufacturer, length of the roll (playing time), and whether the lyrics were printed on the roll. Today, a modern 88 note roll costs around $14 from the QRS company. Piano rolls were produced by either recording the playing of a pianist or pianists using a recording piano ("hand played" rolls), or arranged by perforating the paper by hand using the sheet music as a guide ("arranged rolls"). Many rolls were produced using a combination of the two methods, as the recording piano technology was still relatively primitive, and required post-performance editing.

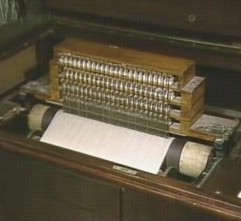

The QRS Company started producing 'hand played' rolls in 1912, using a recording piano developed by Melville Clark and Lee S. Roberts, amongst others. The piano, still in use today, has each of its 88 keys pneumatically connected to a stylus in the recorder (pictured to the right). These styli are suspended horizontally above a roll paper at a point where it passes over a carbon cylinder. When a key is depressed, the corresponding pneumatic collapses, pressing the stylus on the moving roll paper as it passes over the carbon cylinder, which leaves a mark on the underside. As an artist plays, each stylus marks its note on a roll of paper being pulled over a cylinder covered with carbon paper, faithfully recording the performance. Upon completion of the recording, the carbon marks are cut out and a production master is made from this roll.

-

The Imperial company, who produced rolls in Chicago during the same era, used a different method. Roy Bargy, a noted jazz pianist and composer, recorded many rolls for the Imperial company in Chicago. In an interview, he recalled the recording process: a master roll was made at that time by a large machine with crayons in it which dropped down onto a piano roll about four feet in length and made marks on heavy paper. This master roll was them put into another machine which cut slots in the roll where the marks were. Then the large roll was reduced down to standard size. This roll, called a 'specimen', was played by Bargy on a standard player piano to remove mistakes and make a few corrections to improve the overall effect.

To make these changes, he cut slots in the roll by hand or put tape over undesired slots. He says that embellishments were not added at Imperial - the attempt was always made to maintain the player's original style and only to make improvements.

After this process was completed, the roll, (called a test roll) would be listened to by Bargy and Charley Straight, the production manager, who would make any final adjustments required until they were satisfied. This became the final master roll, which was then put into production.

Both the Imperial and QRS methods of recording were unable to provide instant playback, as the marked roll had to be perforated by hand before it was available for listening. The giant Aeolian Company of New York and London used a 'direct perforating' method, in which a roll was punched as the pianist played. Their Uni-Record brand offers (in the author's opinion) the truest hand played performances , which seem to have been virtually unedited, and punched at the highest punch advance rate of any handplayed rolls of the time. (In layman's terms, the higher the punch advance rate, the more possible locations of each perforation on the paper, providing a more accurate reproduction of the performance).

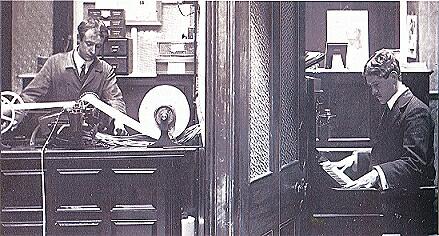

An example of the 'direct perforating' method of recording.

A 'reproducing piano' playing "Blue (And Broken Hearted)", as recorded by Edgar Fairchild and George Dilworth in 1922.

What is a Player Piano (Pianola)?